Real Florida: Red-faced with the Coppertone Girl

It's one of the most memorable ads ever produced, but at 48, its model would like to put those bare buns behind her. Her mother the artist, though, was willing to talk.

By JEFF KLINKENBERG

Published September 5, 2004

OCALA - When I was a boy, growing up in Miami, we often drove across MacArthur Causeway on our way to the beach. Near Biscayne Boulevard, on the side of a downtown building, was the biggest billboard I had ever seen. On the billboard, a dog was pulling down the bathing trunks of a little girl in pigtails.

Eisenhower was still president, and everybody was repressed except maybe those finger-snapping, reefer-smoking, free-sex beatniks in Greenwich Village, so it was shocking to be able to look out the window of our Nash Rambler and see an innocent little girl's butt cheeks being exposed by a rude dog for all the world to see.

"Don't be a pale face," said the letters on the sign. "Use Coppertone."

That ad for suntan lotion was among the most memorable come-ons in perhaps the golden age of advertising. You could see the ad on street corners in San Francisco and in Manhattan, on the blue highways of the Great Plains and here and there throughout the Wheat Belt.

The Coppertone Girl, it turned out, was as American as a Moon Pie. But if you lived here back then, if you lived anywhere near a beach, you considered the ad as quintessential Florida. It was a postcard of sorts that celebrated the sand and the sun and our state as a place where anything could happen.

Recently, I made a telephone call to a woman named Cheri Brand to ask if I could drive up to Ocala and talk to her about the Coppertone ad. There was silence on the phone; reporters learn to dread silence. Finally she said, "Oh, no. Not that. It's so old. You don't want to write about that. Really. Nobody cares."

The Coppertone Girl with the bare cheeks, now 48, was in no mood to bare her soul.

"You know," she said, "you don't want to talk to me. You want to talk to my mother. My mother is much more interesting than I'll ever be. Mother is the real story."

Usually, when somebody says don't talk to me, talk to my mother instead, a reporter comes down with the willies. The gray-haired mother produced by the reluctant interviewee turns out to be a saint who whips up apple butter by the gallon, or a kindly grandma who knits smiley faces on feathery quilts for shivering orphans, or a reincarnated Elizabeth Browning who minutes ago finished writing an 800-line poem about her cat, Slinky, and is looking for a publisher.

Not that there is anything regrettable about quilts, apple butter and cat poetry that always rhymes moon with spoon.

Joyce Ballantyne Brand, 86, was the opposite of an apple butter gal. I did not bring a martini shaker with me to Ocala, but I should have.

More to life than Coppertone

"Mind if I smoke?" she asked in a nicotine voice. "My whole house is my ashtray."

"Mother," said her daughter, the reluctant Coppertone Girl, "be careful of what you say to a reporter. They're always looking for something to make the story better."

Joyce Ballantyne Brand, a commercial artist who gave the world the Coppertone Girl, the Pampers Baby and countless half-dressed women who posed on many a risque calendar, gazed across the table at me through giant pink eyeglasses and the haze of cigarette smoke. I got the feeling she knew how to handle hayseed reporters.

"So whattya want to know?" she growled.

I wanted to know everything, I confessed, from the beginning to now, but especially about the Coppertone Girl that had titillated me as a young boy.

"Be careful, Mother," said her daughter from across the table. "Don't use any swear words."

"Ah, I won't," she said. "But you know, I get tired of talking about the Coppertone Girl. Yeah, it was a good billboard, but it was hardly the only art I ever produced. But that's what everybody remembers. That's what everybody wants to talk about. The Coppertone Girl."

I felt my face grow hot.

"Hey," she said. "Go use the bathroom."

Blushing even more, I stole a quick glance at my fly. Zipper closed, thank God. But I had drunk a quart of coffee on my drive north, so I did as ordered.

In the bathroom I was admired by a life-sized mermaid sprawled in the tub. The sculpture had fine, shapely hips and more than ample breasts.

"Well," Joyce Ballantyne Brand said when I emerged, "at least I didn't make her face very pretty. Otherwise she'd be obscene."

From paper dolls to pinups

So the mother of the reluctant Coppertone Girl told me her story. She said she was born in Nebraska near the end of World War I and liked drawing and making paper dolls; during the Depression she sold paper dolls for a buck apiece. She said she habitually entered art contests and won a scholarship to Disney's School for Animation in California. She remembered the day when the Disney representative heard her girlish, teenage voice over the phone and rescinded the scholarship. Women married and had babies and gave up careers, she was informed. A woman was a poor investment.

"Not the last time I heard that," Joyce growled.

She spent two years at the University of Nebraska and two years at the American Academy of Art in Chicago. She met and married her first husband, artist Eddie Augustiny. She said she drew pictures for dictionaries, did maps for Rand McNally, painted murals for movie theaters and learned to fly a plane. She was barely 25.

"This is what you want to hear about?" she asked. "It's so boring."

World War II began, and even male artists got drafted. Doors opened to women, and her old college professor, the famous pinup artist Gil Elvgren, got her a job at a studio known for churning out the sexiest calendars on earth. Even closing in on 90, Joyce is an attractive woman. As a young woman, she resembled the Donna Reed in From Here to Eternity, only earthier. Often she used herself as a model, gazing into the mirror while painting a buxom doll who later would be admired in a greasy garage by drooling auto mechanics. Today, her pinups are collector items.

She showed me a few. They weren't naked.

"Mine always had some clothes on or at least a towel on," she said in that smoky voice. "I didn't go in for dirty stuff like they do today."

My face grew hot again.

"Mother," said her daughter, the reluctant Coppertone Girl, "tell him your philosophy about pinups."

"The trick is to make a pinup flirtatious," Joyce said. "But you don't do dirty. You want the girl to look a little like your sister, or maybe your girlfriend, or just the girl next door. She's a nice girl, she's innocent, but maybe she got caught in an awkward situation that's a little sexy."

Joyce and her husband divorced. She married a TV executive, Jack Brand, and they had lots of laughs together. He was creative; she was creative. They had their own lives and interests and always supported each other and avoided jealousy.

She used him as a model for a famous ad for Schlitz beer. She did portraits of the well-known and the little-known. Sometimes, when subjects wouldn't relax, Joyce threatened to get them drunk. Whiskey worked wonders.

In 1947, she began a long association with Sports Afield, the outdoors magazine. Her illustrations accompanied the stories. One time she painted a mermaid on the cover. Full of mischief, the mermaid hung boots and tires on the hooks of oblivious anglers. The mermaid - Joyce again had used her comely self as a model - was quite provocative. Some readers objected: How dare she lead men and boys astray in a magazine devoted to an innocent

pursuit like fishing?

Joyce lost no sleep about the complaints.

Interesting, but I brought up Coppertone to Joyce. Tell me about Coppertone.

Well, okay, Joyce said. The boring Coppertone story. In 1959, Coppertone solicited drawings from prominent commercial artists for a new ad campaign. She was given a few examples, stick-figure drawings, to go by. Using her daughter, then 3, as a model, she did a few sketches.

"I made Cheri look a little older and gave her shorter legs. They liked my paintings, and I got the job."

Joyce received $2,500, a good day's work.

"Just another ad," she said. "Just another baby ad. Kind of boring."

Don't ask to see the tan line

Joyce did not do boredom well. The Brands moved to Ocala in the mid 1970s so Joyce could be near her parents, but she hated Ocala. She was used to Chicago. She was used to a penthouse in Manhattan and artsy friends who smoked pipes and drank martinis. It was hot and buggy in Florida. Frogs grunted and alligators roared. People ate grits, for heaven's sake. They ate fried catfish. "Backward. Not even a Federal Express office. I'd go to a paint store for supplies and would literally find a sign on the door that said, "Gone Fishing.' I didn't think I'd be here long."

She and Jack took possession of a grand old three-story building in downtown Ocala. In 1985, Jack developed a cough that was diagnosed as lung cancer. "I could kill him for dying," Joyce told people at the funeral. Recently she gave her sprawling third-floor studio to her daughter, Cheri, and to Cheri's husband, for living quarters. Now Joyce lives on the second floor, which is filled with her art and her memories.

Her daughter helps out when she is not working at the YMCA, where she is a personal trainer. Cheri still has blond hair like she did when she was the Coppertone Girl but doesn't braid it into pigtails. She has a good tan, and I was tempted to ask about her tan line but lost my nerve.

"People can be incredibly boring about the Coppertone Girl," she said. "Sometimes they ask to see my tan line. It's irritating."

I felt my face grow hot.

"People seem very excited to learn that I was the Coppertone baby, and they share stories of how the billboard was a landmark in their memories. In 1993, there seemed to be a renewed interest. I was invited to appear on the Sally Jessy show and Entertainment Tonight. Anyway, that's about it."

The Coppertone Girl's mother told me to follow her. As she showed me stuff, Joyce used her walker to get around her home. She showed me her paintings of circus clowns. She showed me her painting of an alligator. She is painting a portrait of a friend ill with Lou Gehrig's disease and wants to capture the woman's impish personality. She doesn't want a sad painting.

"Too much sadness in the world already."

She will take her time. When you are 86, and you need a walker and have arthritis in your hands, you take your time even if you are 26 in your heart.

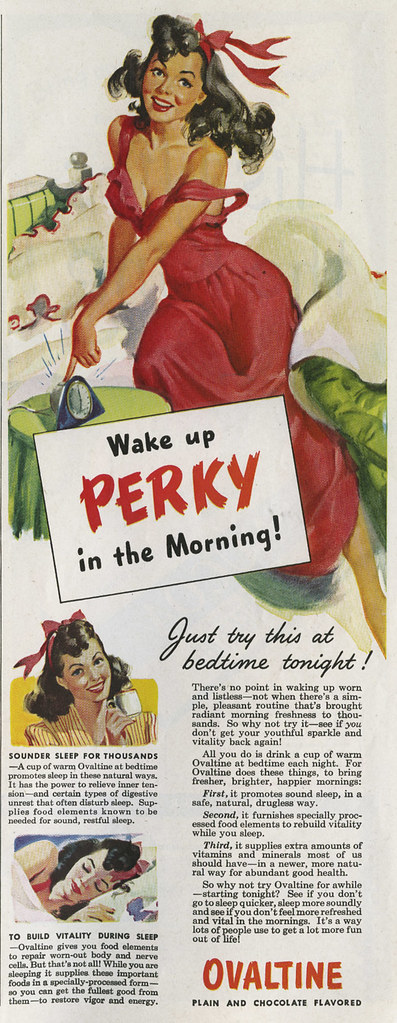

In the morning, she drinks Ovaltine, a habit she picked up when she illustrated an Ovaltine ad in the 1940s. In the afternoon she sips Yoo-Hoo. In the evening - Joyce was always an evening person - she will not turn down a stiff martini.

"I've had my chance to remarry," she said, leaning close and igniting another Benson and Hedges. "Men with money, too. I like men, I value their companionship, but I don't want to get married again."

(SOURCE: St. Petersburg Times)

Researching ephemera sooner or later brings you back around into a circle. It's sort of like playing the Kevin Bacon game. Which by the way I suddenly realized the other day a friend and I could play and we'd be only a few degrees away. I think it was 4 degrees.

________________________